Read this blog alongside the blog Breaking the Ceiling: Teaching Learners to Think Beyond Limits

Here’s what the researchers found in the study “Knowledge Does Not Protect Against Illusory Truth” (Fazio et al., 2015):

- Repeating false ideas makes them feel true, even when you already know they're false.

- Familiarity tricks the brain—it’s easier to process repeated statements, so they start to feel right.

- That means knowledge alone isn’t enough to block the illusion of truth.

- In fact, your brain can ignore what it knows (a phenomenon called knowledge neglect) when something just “feels” correct. cognitiveresearchjournal.springeropen.com+11pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov+11researchgate.net+11

Think of learning a garden path:

Walk it long enough—even if it’s the wrong path—it becomes easier to follow than taking a correct but unfamiliar route.

How This Shows Up in Schools

- Teachers may correct myths like “worksheets equal learning,” yet repeating those ideas makes them feel normal, even when evidence shows they don’t work.

- Learners memorize “procedures” without understanding the why, so when faced with something slightly different, they flounder.

- This illusion lets familiar methods—like syllabus coverage or step-drill fluency—stand in for actual, deep learning.

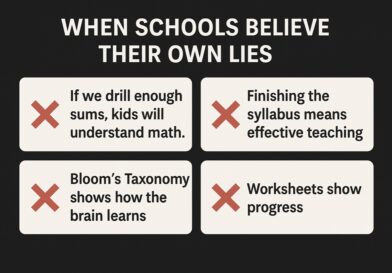

When Schools Believe Their Own Lies: The Illusory Truth in Education

For over a century, schools have sung the same song and stared at the same picture:

Drill the sums. Cover the syllabus. Hand out worksheets. Mark the tests.

And year after year, the results whisper—sometimes shout—this isn’t working.

The Illusory Truth Effect — in simple terms

Our brains have a shortcut:

The more we hear something, the more true it feels—even when we know it’s false.

Repetition makes the brain comfortable. Comfortable feels safe. Safe starts to feel true.

Think of a garden path: walk it every day and it becomes smooth and easy to follow—even if it’s the wrong path.

What schools keep repeating (and believing)

- “Drill more sums and learners will understand math.”

- “Finishing the syllabus equals good teaching.”

- “Bloom’s Taxonomy matches how the brain learns.”

- “Worksheets show progress.”

- “Some children are just not math people.”

We’ve heard these lines for so long that they feel true. But the evidence—learners struggling, freezing in tests, hating math—says otherwise.

Tone deaf and visually deaf

- Tone deaf: Schools don’t hear the warning signals—test anxiety, silence, shallow answers, disengagement.

- Visually deaf: Schools don’t see the obvious—neat worksheets and copied notes that hide zero understanding.

The perfect illusion (math example)

A Grade 6 learner completes 100 long-division problems perfectly on worksheets.

Then the exam adds context: a word problem. Suddenly, they’re lost.

The teacher thinks, “But we drilled this!”

That’s the illusion: drill ≠ understanding. We trained the hands, not the mind. The brain never learned how to plan the plan before executing it.

Why we keep doing it

Because it’s familiar. Familiar feels safe. And repetition tricks the brain into thinking, “This must be right—we’ve always done it this way.”

What’s really happening in classrooms

- Learners can repeat procedures but can’t solve a new-looking version of the same problem.

- After hours of worksheets, they freeze in exams because they were never taught to think, plan, and choose a strategy.

- They memorize formulas but can’t explain why they work.

- They fear math not because they can’t think—but because they were trained to believe math is speed + right answers, not reasoning.

A mirror for schools

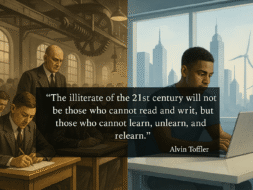

If learners keep failing math exams, hating math, and saying, “I’m just not a math person,” the problem isn’t the learners.

The problem is our loyalty to methods repeated so often they look like truth.

Clearing the window

The illusory truth effect is like a dirty window: you can’t see clearly until you wipe it clean.

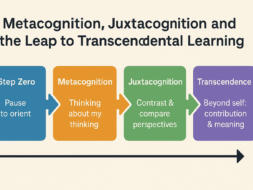

If we want real math learning—not the appearance of learning—we must:

- Question what we repeat.

- Stop worshipping speed and drill as proof of learning.

- Teach for deep understanding: let learners compare, explain, and justify.

- Build planning before execution: help them choose a method, not just copy steps.

- Listen to the alarms—freezing in exams, disengagement, stagnant results—and treat them as data, not background noise.

Math isn’t broken. Our way of teaching it is.

It’s time to wake up. Look closely.

What “truths” have you been repeating without thinking?